December 3, 2021 — The founding members of Bruchim’s executive board join Dan Libenson and Lex Rofeberg for a conversation on the Judaism Unbound podcast about why their organization exists, how opposition to circumcision can come from a deeply Jewish place, and what it might look like for Jewish communities to explicitly welcome people into their communities independent of their circumcision status. This is part one of a series that features Team Bruchim. Listen here!

Podcast Transcript

Dan Libenson: This is Judaism Unbound, Episode 303. “Bris,” means, “covenant,” not, “circumcision.”

Dan Libenson: Welcome back, everyone, I’m Dan Libenson…

Lex Rofeberg: …and I’m Lex Rofeberg.

Dan Libenson: This week we’re excited to be launching a new series of episodes looking at the question of circumcision. Now, we’ve been meaning to do these episodes for a while, but actually it turns out that the topic has been getting airtime and getting on people’s minds, there was an article in the New Yorker not too long ago by Gary Shteyngart, the novelist, about his own experience with a circumcision that didn’t go well. There are a lot of folks who believe that it’s not the right thing to do to circumcise a baby before they’re really able to make that decision on their own. And there are a lot of jews—more than you would think—who have made an alternative decision.

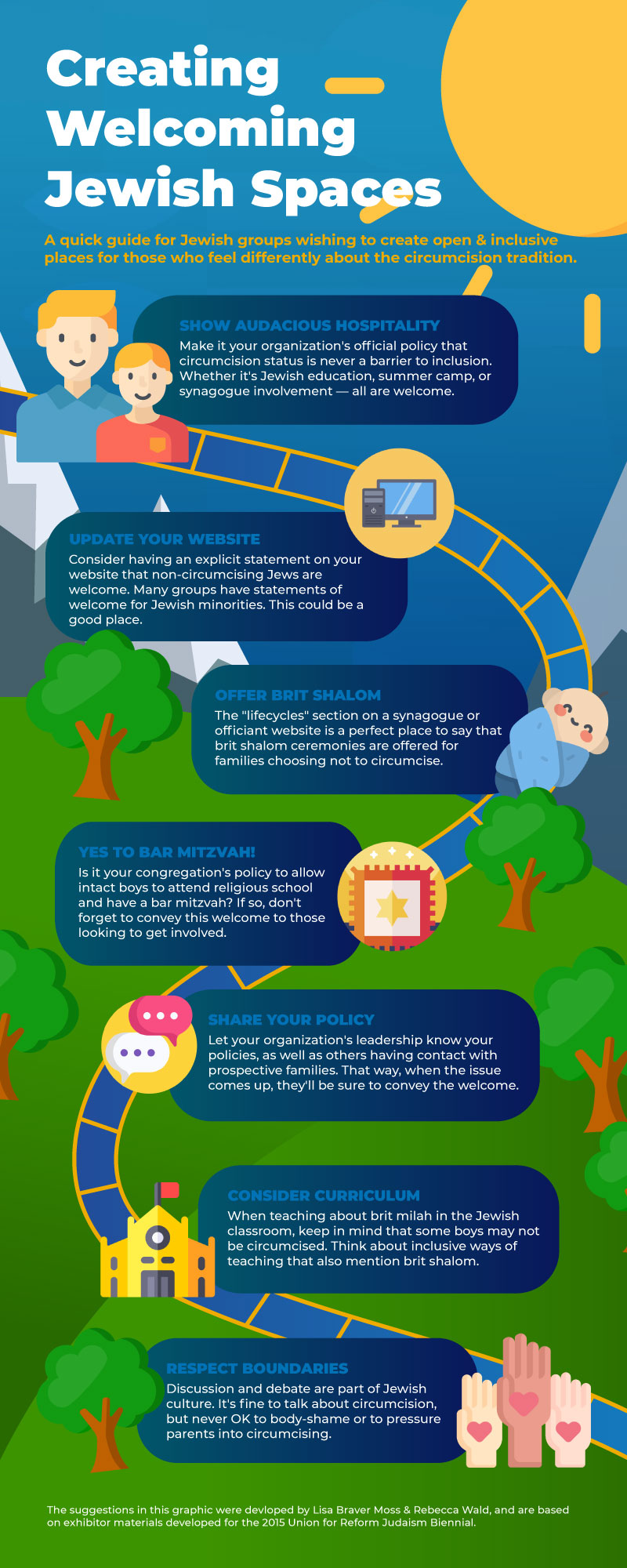

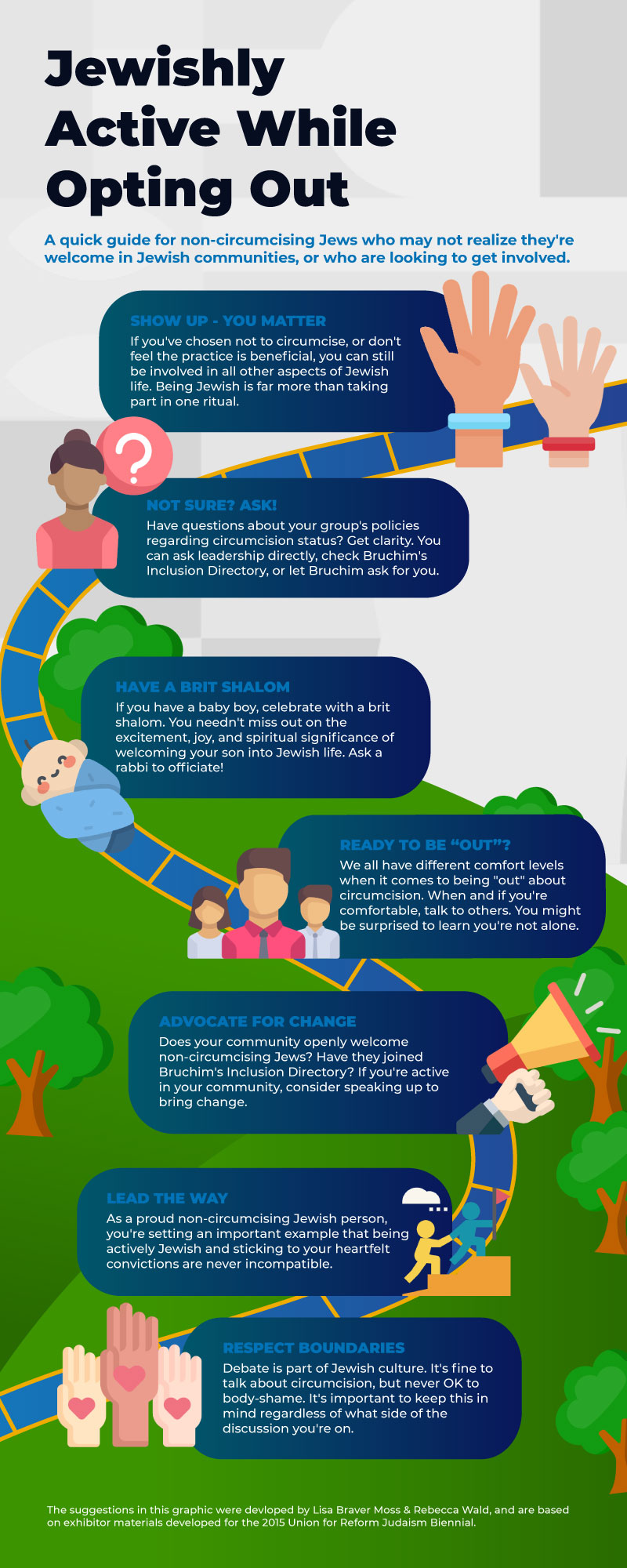

Our guests today are the founders of an organization called Bruchim, whose mission is to expand the numbers of Jewish organizations that are explicitly and outwardly welcoming Jews who have made the decision not to circumcise their children. Bruchim is developing an inclusion directory and also a concierge service to help people find communities that are welcoming and also to help them find officiants that will help them to welcome Jewish children into the community into a different way. Our guests today are the founding executive board of Bruchim, a board which has already begun expanding substantially. They are Lisa Braver Moss, Rebecca Wald, and Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon.

Lisa Braver Moss is the president of Bruchim. She is an award-winning novelist and non-fiction writer who has explored Jewish trauma in her novels, THE MEASURE OF HIS GRIEF, and SHRUG. She published an article called, “A Painful Case,” in Tikkun magazine 1990 and it was one of the first longform pieces to challenge the circumcision tradition from a Jewish perspective. Since then, she has written and lectured and extensively on the challenge of being an active engaged Jew and being a vocal circumcision critic. Lisa Braver Moss has co-published together with our second guest Rebecca Wald, a ritual guide called, “Celebrating Brit Shalom,” the first and only book for parents wishing to hold alternative brit ceremonies for welcoming babies who won’t be circumcised.

Rebecca Wald is the executive director of Bruchim. She is a lawyer by training who has worked as an attorney, a legal news reporter, and a media strategist, and in 2010 she launched “Beyond The Bris,” a Jewish voices website for those who question circumcision.

And our third guest, the third member of the founding group, is Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon. He is a filmmaker with degrees from the school of the art institute of Chicago, and his first feature film was called, “CUT: slicing through the myths of circumcision.” Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon has also produced a feature length documentary called, “A People Without A Land,” and he is the cohost of the four cubits podcast.

Lisa Braver Moss, Rebecca Wald, Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon, welcome to Judaism Unbound, it’s so great to have you!

Lisa Braver Moss: Thank you so much!

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: Thanks, Dan! It’s a pleasure to be sharing these rarified airwaves with you.

Dan Libenson: Well, Eli, actually I want to start with a comment about our history together. I was first introduced to this whole topic about fifteen years ago. I was a new Hillel director, and we were trying to do something that would be unexpected, to show there was a new sheriff in town, a new team shaking things up. And one of my staff members was friends with you and said, “I have a friend who just finished a film that’s about circumcision…but it’s kind of against it.” And I said, well that sounds good! And we hosted the screening, and I learned a lot in those early days about a topic that I had not really thought very much about.

But Lisa, I wanted to start by asking you—that even as early as 1990, you had already written an article in Tikkun about this topic and I’m wondering if things were happening even earlier than that. Can you give a bit of the history about this whole movement, this rethinking of the role of circumcision in Judaism?

Lisa Braver Moss: Yes! Thank you so much for asking, Dan, and I’m just delighted to be here.

I have two grown sons, they were both born in the late 1980s, so that was when it was really first on my mind. They’re both circumcised which I agreed to reluctantly. I always had qualms about circumcision, but I thought about it as something almost transactional, the price of Jewish belonging. And also, it turned out, it was also the price of not having a major conflict with my husband. So, this was not quite the covenant that genesis 17 describes. But anyway, I’ve learned a lot since then and the more I’ve learned the more convinced I am that circumcision is at best unnecessary, and at worst quite harmful.

It was not a positive or affirming way for me to enter into this daunting territory of motherhood. Traditions are meant to bring us together, but I didn’t feel more Jewish because of circumcising my sons. I didn’t have the consolation that this is god’s will because I didn’t believe it was god’s will for me to circumcise. I certainly didn’t circumcise with the required kavanah—spiritual intent—but I somehow couldn’t bring myself to let it go. I began to immerse myself in the halakha about circumcision so that I could write about it. I think that was my way of insisting that my experience was and should be part of the Jewish conversation. I wanted to be “included,” in today’s parlance. So, I began looking for arguments against circumcision that were consistent with Jewish law and Jewish thought.

Interestingly, it was through this process that I became much more engaged in Jewish life. I studied for an adult b mitzvah, I began hosting shabbat gatherings, I began to feel part of the Jewish community. And by the way, my husband has come to agree with me about circumcision and we have a new baby boy in our family, our first grandchild, and my son and daughter-in-law decided to welcome him with a brit shalom ceremony instead of circumcising. And for anyone who doesn’t know, “brit shalom,” means “covenant of peace,” and it’s a ceremony specifically designed for non-circumcising Jewish families.

Dan Libenson: So, I have a small question and then slightly a bigger question. The small question is, to clarify: when you said, “I wanted there to be a place for me in this conversation,” did you mean, and I’m sure the answer will be both, but did you mean you as a regular Jew, a non-Rabbi, or did you mean you as a woman and a mother?

Lisa Braver Moss: It is all above the above. It had to do with really wanting to engage Jewishly and wanting to have a Jewish conversation because there are plenty of opportunities to have conversations about circumcision that are not Jewish, and that’s a difficult territory, a difficult terrain because there are issues specific to Judaism which need to be talked about within Judaism but there really wasn’t a lot of dialogue at that time in Jewish life.

Dan Libenson: It just strikes me that Benay Lappe has famously said that if you’re drawing your paycheck from what she calls, “option 1,” which is the old way, then you’re not going to go, “option 3,” which is what she describes as a profoundly new way. It just strikes me that this is a great example of a topic that you can imagine that there are going to be male rabbis out there and I know there are already, but that would say, “hey I don’t know if we should talk about this.” But so much of what you describe…it’s the way that I felt when we were having the circumcision for my son. It wasn’t that I had this strong objection, it was more like, well that didn’t feel beautiful! You know, and my wife was exactly the same as you described it, it was a horrible experience in the sense of just feeling empathetic and terrible about what happened. And so, you kind of think, like, part of the way that this hasn’t been analyzed in a deep way is because the people who are feeling bad about it are kind of not at the table to have the conversation.

So, could you just say a little bit more about what you did in those early days, and how you dug into it, and what you found?

Lisa Braver Moss: Yea, I first dug into it at the JCC library in San Francisco where I became a regular. And I used to go in there and look at the responsa literature, look at the halakha. I had questions about causing pain to living creatures, I had questions about “welcoming the stranger,” which is in the holiness code. The concept of welcoming the stranger is mentioned, I think, around 36 times in the Torah. There’s a way in which the baby is kind of a stranger. We don’t know the baby yet and I kind of wanted to explore that. And so, I put all of these ideas together into an article for Tikkun magazine and that’s how I started. And then I began speaking about it, and so on. But that’s how I started. I wanted to articulate arguments that were consistent with Jewish thought and Jewish law. I really wanted to not be able to be dismissed as, you know, overly emotional, or “this is just a mother who’s unhappy,” or anything like that. Getting the tone right was a big undertaking for me. I learned a lot.

Lex Rofeberg: I think in this conversation, we’re going to have healthy amount of jumping between some of the ways that this issue has been confronted in the past and now more recently. I really appreciate you talking about this in the late 80s. But for Eliyahu, and Rebecca, I’m curious to hear your entry into this covenantal conversation, this rethinking of our covenantal rituals, and in particular I want to jump to the present. There’s a new project that the three of you have founded, called Bruchim! Which, A, is a cool name, which I won’t define, I’ll let you define it. But you’re creating a project together and it’s not just the three of you. You’ve already got quite a team pulled together, and I’m curious to hear—clearly there were a set of steps from the stories Lisa described (and I love how, by the way Lisa, that for you confronting the problems that arose for you around circumcision actually was an entry way into Jewish experience which is not how people tend to talk about it) but there were clearly some steps between that and ah! It’s 2021, there’s a new organization that’s coming together. Eliyahu and Rebecca, what happened next and how are we doing now in terms of creating an organization for taking Lisa’s origin story and sort of channel it out and help people see themselves in it?

Rebecca Wald: My dad is a retired psychiatrist, and throughout his working years he practiced a therapy that came out of the work of a Jewish physician and psychiatrist named Wilhelm Reich. And he was among the first to recognize that how we’re treated as infants and young children has a lasting impact on us throughout our lives. Reich advocated for newborns to be treated with kindness and he spoke quite passionately against infant circumcision. So, my personal story is that I was first introduced to the idea that circumcision wasn’t such a good thing to do to a child from the books in my dad’s office. And, you know, not long after my first child was born, I really felt compelled to bring this issue to the Jewish community. It felt wrong for me to quietly opt out and then do nothing to educate other Jewish people about what I perceive to be the harm. And I think I also really thought about what the Jewish future might look like when my son was grown, when he was a man, with his own Jewish children who might well not be circumcised. So, I felt a yearning to play a role in shaping that future and I was also very curious to connect with other young Jewish parents who also weren’t circumcising. So, in 2005, around the time that blogs were really starting to take off and get popular, I started a blog called “Beyond the Bris.” And that’s really how things got rolling for me. And I’ve been very fortunate to have a diverse group of writers to share their perspectives and in fact, that’s how Lisa and I first connected. She had written her novel and asked if I would be interested in reviewing it. I did that back in 2011 and that’s how we connected. And that’s the beginning of the story of how we started working together.

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: Yea, my approach to this issue comes form a slightly different place. I come from an orthodox background and for me circumcision is one of those issues that really encapsulates that situation where I think secular humanist ethics come into conflict with the Jewish tradition, come head on into the Jewish tradition. And so, it was the subject of my first feature length documentary when I graduated art school. Dan decided to have the world premier at his university of Chicago Hillel, and I cherish those memories. But for me, this kind of perspective on it, coming from an orthodox background, being actually very committed to my Jewish identity and to my Jewish values but also really happy to engage in that struggle, in those points of friction, that’s where I was coming at this issue from.

I met Rebecca and Lisa for the first time I think in 2011. They came to my San Fransico screening of “CUT,” they sat on the panel, and we got along famously. And what happened from my perspective and sort of my biography, my journey through this issue, is the intactivist (intactivist is a portmanteau between “intact” and “activist” and that’s what anti-circumcision activists like to call themselves. It’s part of a sort of positive rebranding) …the intactivist world embraced me at first and I made lots of great friends, some of whom remain great friends to this day, but I do have to say that in about the sort of 2015-2018 timeframe there was a bit of a shift and there was some much more vocal antisemitism going on in certain intactivist circles. And it was being tolerated by the movement leaders, they were not disciplined about it. And I spoke out about it, of course, because that’s me.

But fast forward to the founding of Bruchim and I was in a place where I was very alienated from the intactivist movement and was looking for a place both to talk about this issue in a way that I didn’t feel was polluted by bigotry, and it wasn’t just the antisemitism that was being tolerated, it was also racism, sexism, and homophobia. And I wanted a specifically Jewish place to talk about this stuff. So, when over the pandemic Lisa and Rebecca approached me with this idea for an organization, and what we want to do is pivot away from talking about the ethics of circumcision and towards talking about including families who have already made this decision. I was like, I’m in. I was all in! I thought this was a great idea and we decided to call it “Bruchim.” Bruchim, in Hebrew, literally means, “those who are blessed,” but it is also part of the Hebrew phrase, “Bruchim habaim,” which means, “welcome.” So, that’s our name, Bruchim!

Lex Rofeberg: That’s awesome! Ok so, I didn’t actually make the connection to the phrase, Bruchim habaim, that’s very cool. I want to sit with something that’s come up in a few different ways, not just with circumcision but with a lot of Jewish stuff, to use a not particularly fancy word. There’s a notion that on this podcast I think we try to combat in a bunch of ways. There’s this notion that Judaism is made of a set of rituals and texts and whatever, so with circumcision says, circumcision is maybe “the Jewish thing,” such that if you don’t like that thing then you don’t like a Jewish thing and you don’t like Judaism. Especially if circumcision is tied to being the core defining marker of Judaism which some might agree, and others might not.

But I approach everything related to Jewish ritual, every Jewish everything, differently. I actually don’t think that to oppose a particular Jewish ritual is un-Jewish. I think to oppose a particular text or ritual is actually extremely Jewish! I think the thing that would not be Jewish would be to not engage with it at all! So, I think it’s actually not surprising in the least that for each of you in different ways, wrestling with circumcision has skyrocketed your involvement in Jewish projects, and even made you co-founders of a Jewish organization, Bruchim.

And so, I’m curious to hear a little more from you about that. Not because I think our listeners out here don’t get it. I think our listeners do get it. But I want them to see themselves in the story of, having a problem with a Jewish story actually is a Jewish feeling to have.

Rebecca Wald: I think that there’s a commonly held belief that infant circumcision, because it’s the one thing that virtually all Jews still do, it’s what’s holding us together as a people. I think that this is a logical fallacy. What follows is this incorrect assumption that if a large enough subset of our population stops circumcising that we’re essentially going to lose our peoplehood. If you’re someone who believes this, then the concept of not circumcising becomes incredibly threatening. I’d like people who think along these lines to consider that circumcision may not in fact be the one thing that’s holding us together. That for many of us, it’s just something we do. Something that’s been part of our culture and our tradition and that the Jewish people may very well be just fine, maybe even better off, when some of us stop.

For a great many Jewish people, circumcision is actually preventing us from engaging more deeply as Jews. And there are a lot of ways that this can happen, but I’d like to mention one in particular, which is that for the very religious who believe this is a divine mitzvah and do this as an act of faith, brit milah is the beginning. It’s the starting point of their child’s religious life. But for many other Jews, infant circumcision isn’t the starting point, it’s actually the end. And so, if parents have the circumcision as part of a bris or in a hospital, a box gets checked and the family quickly moves on. And parents can feel good about themselves as if, “I’ve done my duty as a good Jewish parent.” And that’s it for their Jewish engagement.

And of course, since infant circumcision happens to be in line with the American Christian majority, it’s all quite good from any social/religious angle. So, for this situation which probably applies to many American Jews, I think that circumcision can be holding us back from engaging more deeply with Jewish practice. There’s also another aspect to this, in a slightly different domain, for those who aren’t very engaged circumcision can feel like the “be all and end all,” of Jewish identity. Because in many cases, it is. It’s the only thing they’re doing.

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: Rebecca, Lisa, and I have all been having conversations around circumcision for a long time. We’re all veterans of this conversation and you get to see certain patterns emerge. In the orthodox world, where I’ve had a lot of conversations, you get two kinds of approaches. One is the kiruv approach. Kiruv is this orthodox concept of, “we don’t want people falling into secular identities, so we need to do things to persuade them to come back into the fold.” That’s one approach. The other approach is the sort of, “package deal,” concept, a more angry approach, which holds that Jewish law and Jewish observance is a kind of package deal, wherein you should take it all or you should leave it all. In the orthodox world those are the way the responses vacillate back and forth. I think these are both terribly awful, horrendous ways of reacting to people who are critical of circumcision.

But what we’ve found during our monthly Bruchim meetings that have been happening over zoom during the pandemic, (which have been growing over time, which is also fascinating) and what we’ve found is that they are lots of Jews who are alienated from their Jewish identities and from Jewish communities because of how they feel about circumcision. And in this ironic twist, we’ve been functioning almost like that concept I was just describing, of kiruv! Of bringing them back in to a space that’s completely Jewish where they can feel comfortable questioning this tradition!

Lex Rofeberg: The three of you have channeled the spirit of questioning, of upping your relationship to Judaism through that questioning of this circumcision ritual into the creation of Bruchim. And I’d love to hear, where are we now? What is Bruchim?

Rebecca Wald: Bruchim’s mission is to advocate for Jews who don’t follow the circumcision tradition, especially as they’re going out and affirmatively seeking Jewish engagement. And what this really comes down to is helping to overcome the many barriers to involvement. Those who decide not to circumcise often run into things that prevent them from being Jewishly involved. So, for example, parents may want to have an alternative bris for their child instead of a brit milah (a ritual circumcision), but they might not know where to go, or if their Rabbi approves of this and will officiate. And if they ask their Rabbi and are told no, or are given an unwanted lecture, the parents have essentially outed themselves and things can be very uncomfortable. It can even be impossible in some cases, going forward.

Maybe parents want to send their diaper age child to a Jewish preschool but they’re not sure if the caregivers there will be familiar with the appropriate care of the natural anatomy or accepting of their child’s difference. For older children, depending on the congregation sometimes there’s a policy which can be stated or unstated that children who have not been circumcised cannot have the honor of a b mitzvah. And when Jewish institutions have policies that aren’t clear and open, parents can really live in a place of uncertainty, unsure of whether they’ll be accepted or scolded or maybe even outed or expelled as sometimes happened, and this not knowing can really lead some to decide not to engage fully or at all.

I’d like to mention one more thing, which is that Bruchim isn’t just about asking for clarity or for permission with regard to aliyah, or b mitzvah, or being able to find clergy who will officiate at a brit shalom; it’s really recognizing that not all children, teens, and adults in the community have had a circumcision or find this to be a joyful Jewish event or subject. And it’s also not just about us asking like, “please include us.” It’s about asking the question; how do we still show up? And how do we still engage even when our feelings don’t align with the majority.

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: The Jewish community can’t afford to exclude us! We’re in multiple global crises going on right now. You can’t afford to exclude people who are passionate, ethical, committed Jews, from the community over something like this, because you need us!

Lex Rofeberg: So, I guess the question I’d ask is: if somebody out there listening to this podcast is, for the first time, thinking through this set of question on circumcision, and considering whether it’s alternative rituals for their own children, or just changing their perspective on the ritual more generally, what kinds of steps might somebody take to shift the terrain on this conversation so that in 10, 30, 50, or 100 years there isn’t the same level of taboo and we’re actually able to relate to this in a healthier way.

Rebecca Wald: For those who decide to opt out, I think it’s important not only to show up but also to self-advocate when you feel comfortable doing so. And to have joyful alternative brit ceremonies for babies and really just be full participants in Jewish life in the spaces where you wish to be. You know, no matter how the landscape shifts on this going forward, my sense is that there will be an on-going need for Bruchim, or for organizations like it, because thousands of years later we’re still talking about brit milah, and my hope is that thousands of years from now we’ll still be talking about brit shalom.

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: I think a lot of people don’t know what being an “arel,” means in Jewish law. “Arel” is a Hebrew word, it’s a technical word in Hebrew law, which means uncircumcised, or intact. I feel like a lot of people have this misconception that if you are not a circumcised Jew, if you’re an arel, that there are lots of things you can’t do. It’s just absolutely not true. It’s just absolutely, categorically untrue. And not only is untrue, but I can also demonstrate this from the heart of the Rabbinic tradition that you can’t assume based on the knowledge that a Jewish male is not circumcised, anything else about their Jewish practice. So, when you find out about communities or Rabbis who are excluding Jews and publicly shaming them over this decision, they’re actually not in line with traditional halakha! They’re employing what some would call a meta-halakhic concept, which is just another word for politics.

So, giving people the tools to understand these texts actually, actually engaging with the Jewish text, and using video and animation and music and sound design, to make it more accessible…I think people will be able to form their own challenges. They can go up to their Rabbi and say, “what you’re saying to me is not in line with halakha! And here are the texts.” Fostering that kind of an engagement can only have a positive impact on the Jewish people and on the Jewish future.

Lisa Braver Moss: We’re seeing a different conversation already in the Jewish community because we’re proposing this idea of including these families and including this in the Jewish conversation. It has shifted, and we notice this in the press and in the interviews that we’ve done, that somehow speaking about inclusion has made it easier to speak about this issue. And that certainly is what will make more people think about not circumcising as an option.

Dan Libenson: I’m still not sure how to embed or educate the American Jewish people on certain concepts. For example, there’s so many people who go around and say, “well, I’m kind of Jewish but I was never b mitzvahed, so I’m not really Jewish.” People have this concept that the b mitzvah is a thing that is somehow more than a coming-of-age ceremony that marks a transition, they think it is the transition, and if you don’t have one, you haven’t made that transition and are not “a real Jew.” A lot of people know that that’s wrong…something we learned from a past guest on the podcast was that the b mitzvah actually comes from demand from regular Jews, not Rabbis, who actually wanted something more analogous to what they saw in America around them, like a sweet sixteen. At least, the b mitzvah as we know it, with the big ceremony and the party. In the old days it was just you came up to the Torah, said a blessing, and had some schnaps…And of course, even if you didn’t do that, you were still fully a Jew. But the whole idea that you have to do all these modern things is not only an innovation, it’s an innovation driven by the demands of regular people who wanted to have big parties like their neighbors, and somehow that boomeranged and made the people who aren’t doing it feel like they aren’t Jewish, and it never came from the halakha in the first place! It never came from any Rabbi.

Here, with brit milah, even the most orthodox—right, look in the Talmud and other halakhic sources—just because you’re uncircumcised doesn’t mean you’re not a Jew. But there’s layer upon layer of misconceptions. So, for example, even if the Talmud did say something like that, there’s a million cases in the Talmud where they overturned Torah rules and Torah principles because there’s something in their society that makes those principles no longer right. In another show that I do, we just spent 10 or 12 weeks studying the eye for an eye text and we found that the Rabbis just said, “we don’t like that idea so much anymore and let’s just not do it anymore.”

I’m wondering if you could give us some more, of both conversations you’ve had with regular Jews on the ground, and also maybe with Rabbis, and maybe across the denominations. Because I’m thinking about how there’s two groups of people. There are people who are very much believers in the old style of Judaism. And that might be one conversation, and that’s maybe a difficult conversation. But I think about the huge numbers of people—probably most of our listeners out there—who don’t really believe that there was a covenant between god and Abraham where there was a personal god who talked to a guy named Abraham and they made a deal where Abraham had to circumcise his offspring and then god would protect him…I don’t think they really believe that. I think they think it’s a story, a myth, perhaps an important story from our tradition but they don’t really believe that that happened or that god is like that. At the end of the day, my question for them is like, what do you think would happen if you didn’t circumcise your child? Do you really think it’s a violation of the covenant? You don’t believe in the covenant in that way.

So, I guess my question is, what is going on in the world of regular Jews our there who feel this intense pressure to circumcise their children but in the end of the day couldn’t really tell you why?

Lisa Braver Moss: I think that don’t ask don’t tell is the way things are now. That plays a role. We have a situation where Rabbis, even some that I’ve spoken to, one in particular, when I asked, “have you done a brit shalom ceremony?” He looked at me, and he said, “I don’t know.” And I asked, well what do you mean, you don’t know? And he said, “well, I kind of suspected that they didn’t circumcise the baby in the hospital, but I didn’t ask.” And that kind of perpetuates this idea that circumcision is monolithic in Judaism and so on, but don’t ask don’t tell…this was also evoked in a personal conversation I had with one of the first openly gay Rabbis in the US, who told me when I asked about if they would welcome these families into their preschool…he said, “it’s don’t ask don’t tell.” And there was not a hint of irony in his response. It was just very matter of fact. It was just, sure, we don’t know, we don’t check at the door.

To me, saying we don’t check at the door sort of misses the point. If someone’s choosing not to circumcise for ethical reasons, they should feel comfortable being part of Jewish life, and not feel like they have something shameful that they need to hide. Not that you can really hide circumcision status anyway, because in Jewish preschools there are diaper changes and toilet supervision and so on. But this isn’t something shameful, it isn’t something we have to be secret about. It may be private–but it’s not shameful.

Dan Libenson: I have a friend who has a child who isn’t circumcised. And they were very concerned about sending the child to Jewish summer camp, thinking that somehow, it’ll be noticed, and they’ll be made fun of by the other kids, or something bad will happen, or maybe the camp would throw the kid out because they would someone say that they’re not Jewish enough or whatever…this was actually a camp connected to the Conversative movement. So, you know, there was actually some reason for concern because this is something that they (the Conservative movement) actually believe in, and take seriously, and etc. But at the end of the day, when they called the camp, the camp said, “It’s fine! We don’t check. These are young kinds, they tend to not notice, and now-a-days kids tend to be more private, and our showers have private stalls and etc.”

So, you know it’s kind of like what I think is sort of connected to what you’re saying, Lisa, they actually were very cool about it. But because it wasn’t really publicized, it didn’t really fully have the effect that even they were trying to have because people made a bunch of assumptions. Now, it’s a question about, how, if you for example are the Conservative movement, and you do believe that circumcision is an important Jewish law…how do you be both welcoming and have it really clear out there that people can participate fully if they’re not circumcised but at the same time not diminish the idea that you believe this is an important part of Judaism?

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: I want to say at first, as regards your friend, had they known about Bruchim and had we been up and running at the time, we have something that we call a concierge service. It is for families who don’t want to have that conversation themselves and can go through us. And we can actually contact the institution and in that way we can serve those families.

Lex Rofeberg: That’s amazing, and I’m just noting to listeners that we will have that listed in our show notes, so if you need it, you can use it.

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: I also wanted to just quickly talk about my sense of where things are right now. We’re having, like I said, these monthly zoom meeting that keep growing and we keep hearing more and more stories, some of which are very disturbing by the way. Much more disturbing than the story Dan just told. I’m talking about people being publicly shamed. I’m talking about a female sibling of a boy who wasn’t circumcised being punished by not being allowed to have a bat mitzvah in a synagogue. Really, kind of out there things! You’ll be hearing more of those stories from us as time goes on because we feel very strongly that people need to hear about these things. Because there’s a level at which—and this is true of many taboo subjects—people argue, “Why should we do something about this? What’s the problem? There’s no problem. It’s not a problem.” And trust me, you’ll be hearing from us, because there are problems.

On the Rabbinic level, I’m seeing the same thing that I’ve seen ever since I started talking about this. Which is, people don’t want to touch this issue with a ten-foot pole. And they’re making a very obvious political calculation, that there’s no upside to them engaging with the issue publicly and there’s a whole lot of potential downside. I’ve been seeing that consistently. I’ve actually written about how that happened in the 19th century in the reform movement. There was a minute where this was group of lay people called the “Society of Friends of Reform,” and there was a little bit of momentum against circumcision and because the reform movement was questioning all sorts of other things, this group tried to get them to question circumcision, too. And ultimately, they failed. The Rabbis kept the status-qou of, “let’s not talk about this, we don’t want to be criticized by the denominations further to the right, we don’t want people questioning our identity so we’re going to double down on circumcision.” And sadly, I am still seeing that today.

Now, we at Bruchim feel that the more successful we are at shining a spotlight on this issue and talking about it publicly and without shame, we’re hoping to put some pressure on Rabbis, and we also have a Rabbinic Advisory Council. And for any Rabbis out there listening who do not have shame about engaging in this issue, we want to welcome you to join.

Dan Libenson: So, I think a lot of times when we talk about an issue like this, we talk a lot about what we’re against, and I would like to talk a little bit about what we’re for. So, I wanted to understand a little bit more about your vision and what you’ve created for brit shalom, and how that can actually function as a new way of becoming a member of the Jewish community without regard to what’s also happening surgically?

Rebecca Wald: So, in 2015, we wrote, “Celebrating Brit Shalom,” and even since then, the landscape has changed very quickly. What was so radical about the book is that we intended it to be used by parents even if they couldn’t find a willing officiant. There were very clear instructions on how to perform this ceremony, right down to the challah and the wine and the ceremonial chair. And I think that it’s very much in line with what we’re doing at Bruchim because we were actively trying to solve the problem of inclusion back then! What we were really saying was, here’s everything soup-to-nuts, that you need to do this for yourself if you have to. And even if your own Jewish community pushes you away, somebody somewhere wrote this book for you and wants you to be included in Jewish life.

Maybe at some point our book won’t be so necessary. Because synagogues will place right on the lifecycles page of their website, “we offer brit shalom for babies who won’t be circumcised.” But until that happens, until it’s clear and open and known that these kinds of ceremonies are available to families then the book still have relevance.

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: I also think it’s important to note that there’s a massive gender imbalance that happens around birth in the Jewish community because of brit milah. There’s a kind of sense for example, and I’m sure many of your listeners are familiar with this, if a relative has a boy and there’s going to be a bris then that’s something worth flying in for. But if it’s just a simchat bat, maybe we save on the airfare. And we think that’s terrible! The more emphasis you put on brit milah, the less important women re because they don’t do it. And it’s just sort of a shocking state of affairs…. not to mention the general discomfort that everyone has with brit milah. I can’t tell you how many people have told me over the years, “I am so relieved I had a girl, so relieved we didn’t have to go through this thing.”

And what Lisa and Rebecca have crafted with their beautiful book is an incredible series of different ceremonies is an alternative where we don’t have to have that discomfort and we don’t have to privilege male births over female births.

Lex Rofeberg: First off, I totally hear you on that, Eliyahu, and it’s such an important point. I do want to name that of course there are some women who have had brit milah because they’re trans women. Part of what is making this issue come back into some conversations are the ways in which not only is it problematic in terms of how it has historically marginalized women, it’s also problematic for all the reasons gender reveal parties are problematic, in that the assume the eternal gender of a child based on what they are assigned at birth. And not everyone continues to identify as the gender they were assigned at birth. Not to reject what you just said, Eliyahu, I just wanted to note it.

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: It’s absolutely an important point, thank you for making it. Also, circumcision deprives a potentially trans person of valuable tissue that could be used to reconstruct their sex organs later in life, so that’s something to think about also.

Lex Rofeberg: So, to bring many reasons why these “alternative ceremonies” like brit shalom, brit rechitza, and others…well, I actually want to start seeing them not as “alternative,” but as wonderful gender-neutral ceremonies. But the last question I have is about…well, not just Jews! So often we look at Jewish history and we think everything is about what Jews or Rabbis or whatever have decided to do. But really, if you look back at the story of Judaism over time, some of the most important things that have changed Judaism forever are, say, like the printing press. That’s not a Jewish thing. The printing press is invented and that changes all of religion, including Jews, a bunch of things become written texts that were not written texts…all sorts of stuff that happens.

We could even talk about the destruction of the temple! The destruction of the temple is an act done by non-Jews to Jews which has an impact on what Judaism looks like for the next 2000 years. And the reason I say all of that is—I believe that the forces in the world that will have the biggest impact on this issue, on brit milah and circumcision, are actually not internal Jewish conversations about what is taboo and what isn’t. But about how the wider society relates to circumcision, religious or not. And you might know more about this than I do but the sense I get is today a different story than one or two generations ago in terms of the extent to which circumcision is just the norm across the board in American society. The sense I have, and please correct me if this is not true, but that more people generally are asking questions about circumcision not because they’re Jews but just because they’re not sure about that practice generally. And there might be trajectories whereby everyone starts circumcising less, and Jews are actually part of everybody, so Jews start circumcising less. I was curious to hear from you on that front. Is that right? Are there’s ways in which that conversation outside of just the Jewish world that the conversation is shifting in ways that might have an impact on the future of Judaism?

Rebecca Wald: I think that’s absolutely right. I think that circumcision is falling out of favor in the USA, in particular. There’s an often-quoted sentiment about the US supreme court that sort of applies to this: courts are not influenced by the weather of the day, but they are influenced by the climate of the era. And this also applies to the court of public opinion. The climate has certainly changed and is changing around the importance of preventing trauma during infancy, and I think the shift away from circumcision certainly has something to do with that. Around the concept of self-determination as well. And the climate is changing because of the ongoing advancement of human understanding of ourselves and our bodies. So Jewish people, in practice, influence non-Jewish people and vice versa. Which is influencing more than the other remains to be seen.

I do think that people look to Jewish people on this issue. The general non-Jewish population looks to the Jewish world to see where circumcision is head. I think that it’s important for the Jewish people to lead the way.

Lex Rofeberg: So, we are about to round out the conversation. I’m just curious as we do so, are there any closing notes you have about brit milah, brit shalom, concepts for people as they maybe wrestle with this issue for the first time?

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: What I would say is: our issues are, to be clear, with infant circumcision. If a person chooses to have this done as an adult, that is beyond the scope of our concern. We have absolutely no problem with an adult making this decision. And from a Jewish ritual perspective I’ve made the argument that there would be benefit to that because the person would be consciously engaging in the mitzvah as opposed to having something done to them at an age when they’re not fully aware of what’s happening. It’s an important point to make because there are situations that arise around circumcision that have to do with adults. You could talk about circumcision for converts. I find them much less problematic, to be honest, it’s a completely different ethical situation. If Jewish denominations decide to say to someone, “if you want to join us as an adult, you need to sacrifice this part of your body.” Would I make that decision? No. But ethically I am not offended by it. My sensibilities are not pricked by it as they are when considering doing it to an infant.

Lex Rofeberg: Thank you all so much for joining us, this has been a fantastic conversation. You know, when I think back on the purpose of our podcast and the kinds of topics we hope to open up and get people’s thoughts rolling, this is precisely the type of conversation that we wanted to have. So, thanks for bringing a provocative but really, I think, important and thoughtful conversation to our podcast.

Rebecca Wald: Thank you so much for having us. We are all listeners of the show, and the work that you’re doing on Judaism Unbound is extremely important, so we feel very honored to have had this opportunity. Thank you!

Eliyahu Ungar-Sargon: We can’t wait to hear your next episodes!

Lex Rofeberg: Same here, we also can’t wait. We hope that you’ll listen next week to the second part of our deep dive into the topic of circumcision, which is just as thoughtful as this one. For our listeners out there, head to Bruchim’s website, bruchim.online and there you can find all sorts of good things. You can learn more about the organization, you can access the concierge service if you are looking to connect to a Jewish organization but are looking to remain anonymous.